The pandemic has brought many changes in how people work. Some lost their livelihoods and others, depending on what they do, now work in a hybrid way, with time split between working from home and in the office. As well as these changes, there has also been a greater focus on health and wellbeing across organisations.

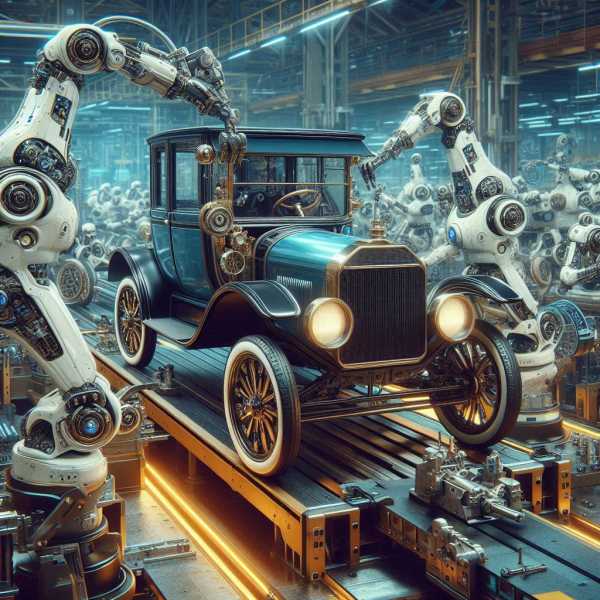

The first organisations were teams of hunter-gatherers, who lived and worked together in small nomadic groups. People played distinct roles and brought together diverse knowledge and experience, so the whole was greater than the sum of the parts, which is one of the fundamental reasons why we have organisations. There are still hunter-gatherer tribes, like the Yanomami in Brazil and Bushmen in Botswana working the same way today. We were hunter-gatherers for around 90% of our history, living in extended social groups of up to 150 trusted or well-known people. The anthropologist Robin Dunbar showed that humans can comfortably support up to 150 relationships. If the number increases beyond 150, we lose the capacity to really know and trust people well enough. This research also supports good practice for organisational design. For instance, the Gore-Tex waterproof clothing company found that they were less productive when more than 150 people worked together at the same location. Like a “golden ratio” for how people work well together, Gore-Tex uses the principle to make sure that “everyone knows everyone”, improving social cohesion and making the company more effective. This helps to explain why some large organisations in the past, who were ignorant of this principle, tended to use a command-and-control style of management, which assumes that people cannot be trusted, so need to be coerced by authority to carry out a task. Some leaders like Henry Ford saw people as little more than machines, and said, “Why is it every time I ask for a pair of hands, they come with a brain attached?”

From a human perspective, this management mindset tends to be simplistic, limited, cold and hard. It avoids the warm, soft, and rich complexity of what it means to be human. There’s no space, openness, understanding, or compassion for what people think and feel. While this may have worked for early car production, it’s out of place in the globalised, digital workplace of today, where autonomy, emotional literacy, and the ability to work effectively with others are vitally important. Apart from a few innovative new organisations, most are still slowly evolving to adapt to the new realities and so have a mix of different management styles. In the best case, the old-school mindset shows poor emotional literacy and communication skills and in the worst case turns a blind eye to bullying and inequality. So, it’s no surprise that research shows a greater rate of sickness absence against these outdated leadership styles.

Compassion is the ability to feel for what someone’s experiencing by bringing kindness and understanding. Empathy is about feeling with, which means taking on the feelings of others. So, for instance, if someone is anxious, with empathy you are also feeling the anxiety, which may not be the best way to help them.

So how can organisations change to become more open, compassionate, and understanding with their employees as well as customers? One way is to promote compassion within leadership behaviours and organisational culture. There is good evidence that compassionate leadership leads to improved employee wellbeing, satisfaction, and commitment. Another is to use the practice of mindful compassion to improve emotional literacy and relationships at work.

Promoting and practising mindful compassion at work makes a difference as it:

- Includes the broader dimensions of human experience, the mind, emotions, body, senses, and relationships

- Helps people become more aware of, and understand their own emotions, as well as how other people feel

- Helps people understand the important role that emotion plays in our lives; driving us to act, alerting us to something that needs attention, and showing others how we feel

- Allows us to see things from another person’s perspective, walking in their shoes

- Makes us more open, patient, generous and understanding; giving people the time and space to be heard

Now that actual robots are building cars, people no longer need to be treated like machines. We need to learn the lessons from how we evolved and maybe work in smaller groups with shared trust and understanding. And on a personal level, relating with other people with connection, openness, and kindness; acknowledging that everyone experiences difficulties and negative emotions and has a rich and complex inner life just like your own.

Suggested weekly practices

- Be aware of any stress of difficulties that colleagues may be going through at work and in their home lives and bring openness, kindness, and compassion.

- If there is someone you are having trouble with, work towards building a more compassionate, relationship with them by walking in their shoes and seeing them as a complete person just like yourself.

- Reflect on how many people you know and have built trust within your social network at work. Is this close to Robin Dunbar’s number of 150 people?

Guidance

Find somewhere undisturbed and sit in a comfortable, dignified and upright posture, where you can remain alert and aware.

There are two guided practices for this session. You can close your eyes, or lower your gaze while the meditations play.

- Play the first settling practice, then read through the session content, which you can print off if that helps.

- Then play the second practice to explore and experience kindness and compassion to others, even strangers and people you do not particularly like.